Words

Words of comfort for myself. Strange that words have such a central part in my life. Peace.

The purpose of spiritual practice is to fulfill our desire for happiness. We are all equal in wishing to be happy and to overcome our suffering, and I believe that we all share the right to fulfill this aspiration.

When we look at the happiness we seek and the suffering we wish to avoid, most evident are the pleasant and unpleasant feelings we have as a result of our sensory experience of the tastes, smells, textures, sounds, and forms that we perceive around us. There is, however, another level of experience. True happiness must be pursued on the mental level as well.

If we compare the mental and physical levels of happiness, we find that the experiences of pain and pleasure that take place mentally are actually more powerful. For example, though we may find ourselves in a very pleasant environment, if we are mentally depressed or if something is causing us profound concern, we will hardly notice our surroundings. On the other hand, if we have inner, mental happiness, we find it easier to face our challenges or other adversity. This suggests that our experiences of pain and pleasure at the level of our thoughts and emotions are more powerful than those felt on a physical level.

As we analyze our mental experiences, we recognize that the powerful emotions we possess (such as desire, hatred, and anger) tend not to bring us very profound or long-lasting happiness. Fulfilled desire may provide a sense of temporary satisfaction; however, the pleasure we experience upon acquiring a new car or home, for example, is usually short-lived. When we indulge our desires, they tend to increase in intensity and multiply in number. We become more demanding and less content, finding it more difficult to satisfy our needs. In the Buddhist view, hatred, anger, and desire are afflictive emotions, which simply means they tend to cause us discomfort. The discomfort arises from the mental unease that follows the expression of these emotions. A constant state of mental unsettledness can even cause us physical harm.

Where do these emotions come from? According to the Buddhist worldview, they have their roots in habits cultivated in the past. They are said to have accompanied us into this life from past lives, when we experienced and indulged in similar emotions. If we continue to accommodate them, they will grow stronger, exerting greater and greater influence over us. Spiritual practice, then, is a process of taming these emotions and diminishing their force. For ultimate happiness to be attained, they must be removed totally.

We also possess a web of mental response patterns that have been cultivated deliberately, established by means of reason or as a result of cultural conditioning. Ethics, laws, and religious beliefs are all examples of how our behavior can be channeled by external strictures. Initially, the positive emotions derived from cultivating our higher natures may be weak, but we can enhance them through constant familiarity, making our experience of happiness and inner contentment far more powerful than a life abandoned to purely impulsive emotions.

Ethical Discipline and the Understanding of the Way Things Are

As we further examine our more impulsive emotions and thoughts, we find that on top of disturbing our mental peace, they tend to involve "mental projections." What does this mean, exactly? Projections bring about the powerful emotional interaction between ourselves and external objects: people or things we desire. For example, when we are attracted to something, we tend to exaggerate its qualities, seeing it as 100 percent good or 100 percent desirable, and we are filled with a longing for that object or person. An exaggerated projection, for example, might lead us to feel that a newer, more up-to-date computer could fulfill all our needs and solve all our problems.

Similarly, if we find something undesirable, we tend to distort its qualities in the other direction. Once we have our heart set on a new computer, the old one that has served us so well for so many years suddenly begins to take on objectionable qualities, acquiring more and more deficiencies. Our interactions with this computer become more and more tainted by these projections. Again, this is as true for people as for material possessions. A troublesome boss or difficult associate is seen as possessing a naturally flawed character. We make similar aesthetic judgments of objects that do not meet our fancy, even if they are perfectly acceptable to others.

As we contemplate the way in which we project our judgments ¨C whether positive or negative ¨C upon people as well as objects and situations, we can begin to appreciate that more reasoned emotions and thoughts are more grounded in reality. This is because a more rational thought process is less likely to be influenced by projections. Such a mental state more closely reflects the way things actually are ¨C the reality of the situation. I therefore believe that cultivating a correct understanding of the way things are is critical to our quest for happiness.

from An Open Heart by Dalai Lama

Collected Noise

... link (no comments) ... comment

From In Light Of India - Octavio Paz

BOMBAY

In 1951 I was living in Paris. I had a modest job at the Mexican Embassy, having arrived six years earlier, in December 1945. The mediocrity of my position perhaps explains why, after two or three years, I had not been transferred to another post, as is the diplomatic custom. My superiors had forgotten me, and I secretly thanked them. I was trying to write and, most of all, I was exploring the city that is probably the most beautiful example of the genius of our civilization: solid without heaviness, huge without gigantism, tied to the earth but with a desire for flight. A city where moderation rules the excesses of both the body and the head with the same gentle and unyielding authority. In its most auspicious moments--a square, an avenue, a group of buildings--tension turns to harmony, a pleasure for the eyes and for the mind. Exploration and recognition: in my walks and rambles I discovered new places and neighborhoods, but there were others that I recognized, not by sight but from novels and poems. Paris for me is a city that, more than invented, is reconstructed by memory and the imagination. I saw a few friends, French and foreign, sometimes in their apartments, but usually in the cafes and bars. In Paris, as in other Latin cities, one lives more in the streets than at home. I met with friends with whom I shared artistic and intellectual affinities, and was immersed in the literary life of those days, with its clamorous philosophical and political debates. But my secret obsession was poetry: to write it, think it, live it. Excited by so many contradictory thoughts, feelings, and emotions, I was living each moment so intensely that it never occurred to me that this way of life would ever change. The future--that is, the unexpected--had almost completely evaporated.

One day the Ambassador called me to his office and, without saying a word, handed me a cable: I had been transferred. The news was bewildering and painful. It was normal that I should be sent elsewhere, but I was devastated to leave Paris. The reason for my transfer was that the government of Mexico had formally established relations with India, which had gained its independence in 1947, and now was planning to open a mission in Delhi. Knowing that I was being sent to India consoled me a little: rituals, temples, cities whose names evoked strange tales, motley and multicolored crowds, women with feline grace and dark and shining eyes, saints, beggars.... That same morning I learned that the person who had been named ambassador was Emilio Portes Gil, a well-known and influential man who had once been the President of Mexico. Besides the Ambassador, the staff would consist of a consul, an under-secretary (myself), and two counselors.

Why had they chosen me? No one told me, and I never would learn the reason. But there were rumors that my transfer had come at the suggestion of the poet Jaime Torres Bodet, then Director General of UNESCO, to Manuel Tello, the Minister of Foreign Affairs. It seemed that Torres Bodet was disturbed by some of my literary activities, and had been particularly displeased by my participation, with Albert Camus and Maria Casares, in an event commemorating the anniversary of the beginning of the Spanish Civil War (July 18, 1936), and organized by a group that was close to the Spanish anarchists. Although the Mexican government did not have relations with Franco--quite the opposite: it was the only country in the world that had an official ambassador to the Spanish Republic in Exile--Torres Bodet thought that my presence at that political-cultural gathering, and some of the things I said there, were "improper." I will never know if this story is true, but years later, at a dinner, I heard Torres Bodet make a curious confession. Talking about writers who had served in the diplomatic corps--Alfonso Reyes and Jose Gorostiza in Mexico, Paul Claudel and Saint-John Perse in France, among others--he added, "But one must avoid, at all costs, having two writers in the same embassy."

I said good-bye to my friends. Henri Michaux gave me a little anthology of poems by Kabir, Krishna Riboud a print of the goddess Durga, and Kostas Papaioannou a copy of the Bhagavad-Gita, which became my spiritual guide to the world of India. In the middle of my preparations, I received a letter from Mexico with instructions from the new Ambassador: I was to meet him in Cairo. With the rest of the staff, we would continue on to Port Said, where we would board a Polish ship, the Batory, that would take us to Bombay. The news was strange--normally we would have flown directly to Delhi--but I was delighted. It would give me a glimpse of Cairo, its museums and pyramids, and I would cross the Red Sea and see Aden before reaching Bombay.

When we arrived in Cairo, Portes Gil told us that he had changed his mind and would fly to Delhi. Later I realized that he had simply wanted to visit some places in Egypt before taking the plane to India. But in my case it was too late to change the plans: the steamship company couldn't refund my ticket quickly, and I didn't have the money for the plane. I decided to go by ship. Those were the last days of the reign of King Farouk and there were many riots--the famous Shepherd's Hotel was burned down soon after. The road from Cairo to Port Said was blocked at various points and considered unsafe. With two other passengers, I traveled in a car flying the Polish flag and, perhaps thanks to it, we arrived without incident.

The Batory was a German ship given to Poland as part of the war reparations. The crossing was pleasant, although the monotony of the passage across the Red Sea was at times oppressive: to the left and right, arid and barely undulating hills stretched out; the sea was grayish and calm. I thought: Nature too can be boring. The arrival in Aden broke the monotony. A picturesque highway through great rocks led from the port to the city. I wandered enchanted through the noisy bazaars, full of Levantines, Chinese, and Indians, and the neighboring streets and alleyways. The colorful crowds, the veiled women with eyes as deep as the water in a well, the faces of the passers-by as anonymous as those in any city, but dressed in oriental clothes; beggars, busy people, groups talking loudly, laughter, and, amid the throng, silent Arabs with noble features and a forbidding demeanor. Hanging from their belts, an empty sheath for a knife or dagger. They were desert people who had to give up their weapons before entering the city. Only in Afghanistan have I seen a people with similar grace and dignity.

Life on board the Batory was lively, the group heterogeneous. The strangest passenger was a maharajah with a monastic face, who was surrounded by obsequious servants. Due to some ritual vow, he avoided all contact with foreigners, and in the dining room his chair had ropes around it to keep the other passengers from coming too close. Also on board was an elderly woman who was the widow of the sculptor Brancusi; she'd been invited to India by a magnate who admired her husband. There was a group of nuns, most of them Polish, who prayed every morning at five in a mass officiated by two Polish priests. They were on their way to Madras, to a convent founded by their order. Although the Communists had taken power in Poland, the authorities on the ship pretended not to notice these religious activities, or perhaps their tolerance was part of governmental policy at the time. It was moving to hear the mass sung by those nuns and priests on the morning we arrived in Bombay. Before us rose the coast of an immense and strange country populated by millions of infidels, some of whom worshiped masculine and feminine idols with powerful bodies or animal features, and others who prayed to the faceless God of Islam. I did not dare to ask them if they realized that their arrival in India was a late episode in the great failure of Christianity in these lands.... A couple who immediately attracted my attention were a pretty young Hindu woman and her husband, a young American. We quickly fell into conversation, and by the end of the voyage were good friends. She was Santha Rama Rau, the well-known writer and author of two notable adaptations, for the theater and for film, of Passage to India. He was Faubian Bowers, who had been an aide-de-camp to General MacArthur and was the author of a book on the Japanese kabuki theater.

Gateway of India with Taj Mahal Hotel in the back

Gateway of India with Taj Mahal Hotel in the back

We arrived in Bombay on an early morning in November 1951. I remember the intensity of the light despite the early hour, and my impatience at the sluggishness with which the boat crossed the quiet bay. An enormous mass of liquid mercury, barely undulating; vague hills in the distance; flocks of birds; a pale sky and scraps of pink clouds. As the boat moved forward, the excitement of the passengers grew. Little by little the white-and-blue architecture of the city sprouted up, a stream of smoke from a chimney, the ocher and green stains of a distant garden. An arch of stone appeared, planted on a dock and crowned with four little towers in the shape of pine trees. Someone leaning on the railing beside me exclaimed, "The Gateway of India!" He was an Englishman, a geologist bound for Calcutta. We had met two days before, and I had discovered that he was W. H. Auden's brother. He explained that the arch was a monument erected to commemorate the visit of King George V and his wife, Queen Mary, in 1911. It seemed to me a fantasy version of the Roman arches; later I learned it was inspired by an architectural style that had flourished in Gujarat, an Indian state, in the sixteenth century. Behind the monument, floating in the warm air, was the silhouette of the Taj Mahal Hotel, an enormous cake, a delirium of the fin-de-siecle Orient fallen like a gigantic bubble, not of soap but of stone, on Bombay's lap. I rubbed my eyes: was the hotel getting closer or farther away? Seeing my surprise, Auden explained to me that the hotel's strange appearance was due to a mistake: the builders could not read the plans that the architect had sent from Paris, and they built it backward, its front facing the city, its back turned to the sea. The mistake seemed to me a deliberate one that revealed an unconscious negation of Europe and the desire to confine the building forever in India. A symbolic gesture, much like that of Cortes burning the boats so that his men could not leave. How often have we experienced similar temptations?

Once on land, surrounded by crowds shouting at us in English and various native languages, we walked fifty meters along the filthy dock and entered the ramshackle customs building, an enormous shed. The heat was unbearable and the chaos indescribable. I found, not easily, my few pieces of luggage, and subjected myself to a tedious interrogation by a customs official. Free at last, I left the building and found myself on the street, in the middle of an uproar of porters, guides, and drivers. I managed to find a taxi, and it took me on a crazed drive to my hotel, the Taj Mahal.

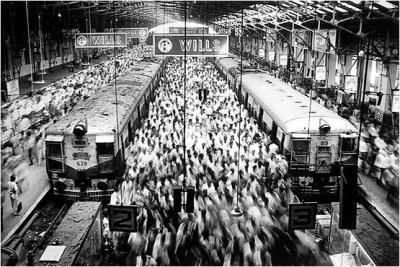

Victoria Terminus by Sebastian Salgado

Victoria Terminus by Sebastian Salgado

If this book were a memoir and not an essay, I would devote pages to that hotel. It is real and chimerical, ostentatious and comfortable, vulgar and sublime. It is the English dream of India at the beginning of the century, an India populated by dark men with pointed mustaches and scimitars at their waists, by women with amber-colored skin, hair and eyebrows as black as crows' wings, and the huge eyes of lionesses in heat. Its elaborately ornamented archways, its unexpected nooks, its patios, terraces, and gardens are both enchanting and dizzying. It is a literary architecture, a serialized novel. Its passageways are the corridors of a lavish, sinister, and endless dream. A setting for a sentimental tale or a chronicle of depravity. But that Taj Mahal no longer exists: it has been modernized and degraded, as though it were a motel for tourists from the Midwest.... A bellboy in a turban and an immaculate white jacket took me to my room. It was tiny but agreeable. I put my things in the closet, bathed quickly, and put on a white shirt. I ran down the stairs and plunged into the streets. There, awaiting me, was an unimagined reality:

waves of heat; huge grey and red buildings, a Victorian London growing among palm trees and banyans like a recurrent nightmare, leprous walls, wide and beautiful avenues, huge unfamiliar trees, stinking alleyways,

torrents of cars, people coming and going, skeletal cows with no owners, beggars, creaking carts drawn by enervated oxen, rivers of bicycles,

a survivor of the British Raj, in a meticulous and threadbare white suit, with a black umbrella,

another beggar, four half-naked would-be saints daubed with paint, red betel stains on the sidewalk,

horn battles between a taxi and a dusty bus, more bicycles, more cows, another half-naked saint,

turning the corner, the apparition of a girl like a half-opened flower,

gusts of stench, decomposing matter, whiffs of pure and fresh perfumes,

stalls selling coconuts and slices of pineapple, ragged vagrants with no job and no luck, a gang of adolescents like an escaping herd of deer,

women in red, blue, yellow, deliriously colored saris, some solar, some nocturnal, dark-haired women with bracelets on their ankles and sandals made not for the burning asphalt but for fields,

public gardens overwhelmed by the heat, monkeys in the cornices of the buildings, shit and jasmine, homeless boys,

a banyan, image of the rain as the cactus is the emblem of aridity, and, leaning against a wall, a stone daubed with red paint, at its feet a few faded flowers: the silhouette of the monkey god,

the laughter of a young girl, slender as a lily stalk, a leper sitting under the statue of an eminent Parsi,

in the doorway of a shack, watching everyone with indifference, an old man with a noble face,

a magnificent eucalyptus in the desolation of a garbage dump, an enormous billboard in an empty lot with a picture of a movie star: full moon over the sultan's terrace,

more decrepit walls, whitewashed walls covered with political slogans written in red and black letters I couldn't read,

the gold and black grillwork of a luxurious villa with a contemptuous inscription: EASY MONEY; more grilles even more luxurious, which allowed a glimpse of an exuberant garden; on the door, an inscription in gold on the black marble,

in the violently blue sky, in zigzags or in circles, the flights of seagulls or vultures, crows, crows, crows...

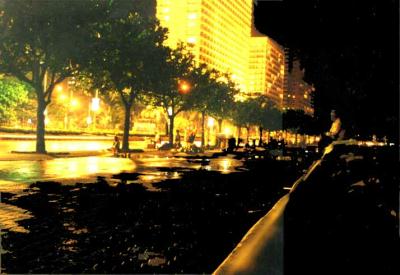

Marine Drive at night

Marine Drive at night

As night fell, I returned to my hotel, exhausted. I had dinner in my room, but my curiosity was greater than my fatigue: after another bath, I went out again into the city. I found many white bundles lying on the sidewalks: men and women who had no home. I took a taxi and drove through deserted districts and lively neighborhoods, streets animated by the twin fevers of vice and money. I saw monsters and was blinded by flashes of beauty. I strolled through infamous alleyways and stared at the bordellos and little shops: painted prostitutes and transvestites with glass beads and loud skirts. I wandered toward Malabar Hill and its serene gardens. I walked down a quiet street to its end and found a dizzying vision: there, below, the black sea beat against the rocks of the coast and covered them with a rippling shawl of foam. I took another taxi back to my hotel, but I did not go in. The night lured me on, and I decided to take another walk along the great avenue that ran beside the docks. It was a zone of calm. In the sky the stars burned silently. I sat at the foot of a huge tree, a statue of the night, and tried to make an inventory of all I had seen, heard, smelled, and felt: dizziness, horror, stupor, astonishment, joy, enthusiasm, nausea, inescapable attraction. What had attracted me? It was difficult to say: Human kind cannot bear much reality. Yes, the excess of reality had become an unreality, but that unreality had turned suddenly into a balcony from which I peered into--what? Into that which is beyond and still has no name...

In retrospect, my immediate fascination doesn't strike me as strange: in those days I was a young barbarian poet. Youth, poetry, and barbarism are not opposed to one another: in the gaze of a barbarian there is innocence; in that of a young man, an appetite for life; and in a poet's gaze, astonishment. The next day I called Santha and Faubian. They invited me for a drink at their house. They were living with Santha's parents in an elegant mansion that, like the others in Bombay, was surrounded by a garden. We sat on the terrace, around a table with refreshments. Soon after, her father joined us, a courtly man who had been the first Indian ambassador to Washington and had recently left his post. On hearing my nationality, he burst out laughing and asked: "And is Mexico one of the stars or one of the stripes?" I turned red and was about to answer rudely, when Santha intervened with a smile: "Forgive us, Octavio. The Europeans know nothing of geography, and we know nothing of history." Her father apologized. "It was only a joke.... We too, not so long ago, were also a colony." I thought of my compatriots: they say similar nonsense when talking about India. Santha and Faubian asked me if I had visited any of the famous sites. They told me to go to the museum and, above all, to visit the island of Elephanta.

The next day I went back to the dock and bought a ticket for the small boat that runs between Bombay and Elephanta. With me were various foreign tourists and a few Indians. The sea was calm; we crossed the bay under a cloudless sky and arrived at the small island in less than an hour. Tall white cliffs, and a rich and startling vegetation. We walked up a gray and red path that led to the mouth of an enormous cave, and I entered a world made of shadows and sudden brightness. The play of the light, the vastness of the space and its irregular form, the figures carved on the walls: all of it gave the place a sacred character, sacred in the deepest meaning of the word. In the shadows were the powerful reliefs and statues, many of them mutilated by the fanaticism of the Portuguese and the Muslims, but all of them majestic, solid, made of a solar material. Corporeal beauty, turned into living stone. Divinities of the earth, sexual incarnations of the most abstract thought, gods that were simultaneously intellectual and carnal, terrible and peaceful. Shiva smiles from a beyond where time is a small drifting cloud, and that cloud soon turns into a stream of water, and the stream into a slender maiden who is spring itself: the goddess Parvati. The divine couple are the image of a happiness that our mortal condition grants us only for a moment before it vanishes. That palpable, tangible, eternal world is not for us. A vision of a happiness that is both terrestrial and unreachable. This was my initiation into the art of India.

Collected Noise

... link (2 comments) ... comment

Earth Day

It was a marvelous night, the sort of night one only experiences when one is young. The sky was so bright, and there were so many stars that, gazing upward, one couldn't help wondering how so many whimsical, wicked people could live under such a sky. This too is a question that would only occur to the young, to the very young; but may God make you wonder like that as often as possible!

White Nights - Dostoevsky

Today they celebrated the Earth Day here at Tech, although the real Earth Day is on Monday, the 22nd. But wait isn't every day we live on this planet an "Earth Day". I wanted to write about my concerns of the environment and the state of the planet as I was walking back here, ofcourse after getting the customary free t shirt. But since eloquence escapes me I give you the words of Chief Seattle to the President of United States. Read them and reflect on how civilization has taken us far from who we are: a thread in the web of life.

CHIEF SEATTLE'S LETTER

"The President in Washington sends word that he wishes to buy our land. But how can you buy or sell the sky? the land? The idea is strange to us. If we do not own the freshness of the air and the sparkle of the water, how can you buy them?

Every part of the earth is sacred to my people. Every shining pine needle, every sandy shore, every mist in the dark woods, every meadow, every humming insect. All are holy in the memory and experience of my people.

We know the sap which courses through the trees as we know the blood that courses through our veins. We are part of the earth and it is part of us. The perfumed flowers are our sisters. The bear, the deer, the great eagle, these are our brothers. The rocky crests, the dew in the meadow, the body heat of the pony, and man all belong to the same family.

The shining water that moves in the streams and rivers is not just water, but the blood of our ancestors. If we sell you our land, you must remember that it is sacred. Each glossy reflection in the clear waters of the lakes tells of events and memories in the life of my people. The water's murmur is the voice of my father's father.

The rivers are our brothers. They quench our thirst. They carry our canoes and feed our children. So you must give the rivers the kindness that you would give any brother.

If we sell you our land, remember that the air is precious to us, that the air shares its spirit with all the life that it supports. The wind that gave our grandfather his first breath also received his last sigh. The wind also gives our children the spirit of life. So if we sell our land, you must keep it apart and sacred, as a place where man can go to taste the wind that is sweetened by the meadow flowers.

Will you teach your children what we have taught our children? That the earth is our mother? What befalls the earth befalls all the sons of the earth.

This we know: the earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the earth. All things are connected like the blood that unites us all. Man did not weave the web of life, he is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself.

One thing we know: our God is also your God. The earth is precious to him and to harm the earth is to heap contempt on its creator.

Your destiny is a mystery to us. What will happen when the buffalo are all slaughtered? The wild horses tamed? What will happen when the secret corners of the forest are heavy with the scent of many men and the view of the ripe hills is blotted with talking wires? Where will the thicket be? Gone! Where will the eagle be? Gone! And what is to say goodbye to the swift pony and then hunt? The end of living and the beginning of survival.

When the last red man has vanished with this wilderness, and his memory is only the shadow of a cloud moving across the prairie, will these shores and forests still be here? Will there be any of the spirit of my people left?

We love this earth as a newborn loves its mother's heartbeat. So, if we sell you our land, love it as we have loved it. Care for it, as we have cared for it. Hold in your mind the memory of the land as it is when you receive it. Preserve the land for all children, and love it, as God loves us.

As we are part of the land, you too are part of the land. This earth is precious to us. It is also precious to you.

One thing we know - there is only one God. No man, be he Red man or White man, can be apart. We ARE all brothers after all."

Love and Peace to All. Sashi

Notes: "In 1851 Seattle, chief of the Suquamish and other Indian tribes around Washington's Puget Sound, delivered what is considered to be one of the most beautiful and profound environmental statements ever made. The city of Seattle is named for the chief, whose speech was in response to a proposed treaty under which the Indians were persuaded to sell two million acres of land for $150,000." -- Buckminster Fuller in Critical Path.

Some more beautiful words: I do not know. Our ways are different than your ways. The sight of your cities pains the eyes of the red man. There is no quiet place in the white man's cities. No place to hear the unfurling of leaves in spring or the rustle of the insect's wings. The clatter only seems to insult the ears. And what is there to life if a man cannot hear the lonely cry of the whippoorwill or the arguments of the frogs around the pond at night? I am a red man and do not understand. The Indian prefers the soft sound of the wind darting over the face of a pond and the smell of the wind itself, cleaned by a midday rain, or scented with pinon pine.

The air is precious to the red man for all things share the same breath, the beast, the tree, the man, they all share the same breath. The white man does not seem to notice the air he breathes. Like a man dying for many days he is numb to the stench. But if we sell you our land, you must remember that the air is precious to us, that the air shares its spirit with all the life it supports. This we know; the earth does not belong to man; man belongs to the earth.

To read the whole speech go here: www.webcom.com

Collected Noise

... link (one comment) ... comment