A world of memory - book review

Paul Farley salutes George Szirtes, a worthy winner of the 2004 TS Eliot prize with Reel

Paul Farley

Saturday February 5, 2005

Guardian Reel by George Szirtes 166pp, Bloodaxe, £8.95

If the city, or a tiny corner of it, was the first place we knew, it is likely to form our notions of reality, and of home. We can lose this first city through the erosions and effacements of development or decline - cities appear to alter more quickly than the countryside. Or we can lose it more dramatically through flight and exile. We can lose them as utterly as a practitioner of Elizabeth Bishop's "One Art": "I lost two cities, lovely ones, and vaster". Yet the city can remain standing in the memory, as George Szirtes's Budapest does.

Szirtes's city is shady, indistinct, blurred at the edges, but his latest collection, Reel, also finds it furnished with closely examined things - a piano, a stove, a child's swing - as well as containing luminous, vivid moments beyond its boundaries. Already celebrated as a translator of modern Hungarian poetry, with Reel Szirtes has now won the 2004 TS Eliot prize for poetry (of which I was a judge). Long admired by his peers, it is to be hoped that this visionary formalist will gain new readers for his own work.

Szirtes's biography has become familiar through his writing over the past couple of decades. Profoundly affected by war - his mother survived a concentration camp, his father forced labour - in 1956, on his eighth birthday, the family crossed the border into Austria on foot at night, following the failed Hungarian uprising. They ended up on the south coast - from landlocked Mitteleuropa to seaside England - treated well along the way, almost as heroes at first: "Xenophobia isn't what it used to be". It would be unusual if such dislocation at such an age didn't present an enduring subject, and Szirtes has returned to his past, or rather his memory of it, repeatedly over the years.

One function of rhyme is mnemonic - for writer and reader - and Reel remembers by deploying end rhyme in almost every single poem. There are traditional shapes like the sonnet, of which in the past Szirtes has proved a deft sequencer, and the sestina, as well as more unusual items, such as "Minotaur in the Metro", which rhymes to its halfway point then back again in reverse, or "Wymondham Wings", which bifurcates Herbert's famous stanzas. There is much terza rima, the very devil of a form: as one door opens, another closes, and I'd suggest interlocking tercets with three rhymes is a bigger ask than sonneteering. It might be the relative paucity of rhyme in English compared to Italian, where everything seems to rhyme with everything else. It could also be the presence of Dante looming over the shape he patented. But Szirtes seems to have achieved lift-off and liberation, like that moment downhill cyclists realise they're being pedalled rather than pedalling. Narrative fragments and images and names come spooling out:

The city is unfixed, its formal maps Are mere mnemonics where each shape repeats

Its name before some ultimate collapse. The train shunts in the sidings, cars pull in By doorways, move off, disappear in gaps

Between the shops. It is like watching skin Crack and wrinkle. Old words: Andrássy út And Hal tér. Naming of streets: Tolbuhin,

Münnich... the distant smell of rotting fruit, Old shredded documents in blackened piles, Dead trees with squirrels snuffling at the root.

Rhyme here even acts as a guide to pronouncing those Magyar place-names in English. If the extent and success of terza rima in Reel distinguishes the book from earlier work, thematically old ground is revisited out of necessity. Szirtes's imagination often seems engaged in the act of rebuilding the city, as in the depressed dystopian "Retro-futuristic", where "there is nowhere to go except the future". There are recognisable shifts of scale and viewpoint, huge stepping backs like "Venice" - "Because there's nothing that will last forever / except perhaps ideas, I think of cities" - as well as immersions in art and cinema. Images and phrases, like his rabbit scuts and unshaven chins, recur both here and across books: perhaps all poets are attempting to find a home for those words or things they find indelible.

Szirtes has always been fond of ekphrasis, a kind of intense description of the visual artefact. As its name suggests, this kind of thing is as old as Homer, and the shield of Achilles, but cinema offered a moving image for writers to renegotiate with. On the other hand, film-makers as early as Eisenstein (writing on Dickens) have recognised how literature long prefigured cinematic conventions. Poetry and cinema can both be said to share a syntax and grammar of close up, jump cut, slow dissolve and flashback, but Reel is notable for the extent to which memory plays out as footage. The materiality of the medium is marked - "bells of the city chime, round upon round. / The film rolls on. A car sweeps round the bend" - and the title poem, which is itself stalked by a film crew, snaps shut "just as the reel breaks".

Whether the omnipresence of cinema and television, or the advent of what Louis MacNeice called "other, less difficult, media" represent a real threat to the written word or not, a part of me is always glad to see poetry keeping up. The appearance of The Matrix and Keanu Reeves (who once played Johnny Mnemonic) made me wonder whether the digitally manipulated image, the whiplash pan, will mark a truer point of separation.

If the cinematic century and its attendant iconography informs Reel, the book also has a classical dimension. As well as its formal organisation of sequence and eclogue, we encounter a mnemon, who would "forget his head if it wasn't screwed on", Sisyphus checking into a hotel, and Ariadne observed by the Eumenides. "Elpenor" is a tender lament for one of those archetypal sweet souls ("There were days he didn't shave / When his embrace was abrasive yet gentle") who wouldn't hurt a fly but come a cropper. You have to search hard for Elpenor down the back streets of the Odyssey, having as he does something of a walk on/fall off part in Circe's palace; though the hung-over young warrior who missed his footing on a ladder was once spoken of in familiar terms by Ovid, Plutarch and Martial, he is largely forgotten now.

Some of the book's most successful moments come when all of Szirtes's preoccupations work in concert, such as "Meeting Austerlitz", a poem-encounter with the late WG Sebald which has great sweep and sadness - "He would unwind / the world of memory and wind it up again / a little off-centre"; or "Sheringham", which must count as an early addition to the sub-genre of internet ekphrasis. The downloaded face of a school friend sharpens as if emerging from the sea on to Arnoldian shingle, and the poem goes broadband into a meditation on time and memory: "I watched a toddler in a red quilted jacket / teeter down stones making tiny forays // onto the black, wet, still sucked-and-licked / lowest tier of them, seeing time itself / contract into a chill in the vast derelict // expanse of the sea that swallowed up each shelf ... "

I wasn't at all surprised to find Szirtes has included three poems based on the work of Sebastião Salgado, that great photographic chronicler of human homelessness, exodus and migration. Even within our less urgent frame of reference, fewer and fewer of us live where our parents did. But for all the technical facility or speculative claims for context, the poems in Reel wouldn't work as well as they do had their arrival not been so deeply felt. "Forgetting is good," "Forgetting is wise," but Szirtes can't.

· Paul Farley teaches creative writing at the University of Lancaster. His most recent collection of poems, The Ice Age (Picador) won the Whitbread prize for poetry in 2002

Collected Noise

... link (no comments) ... comment

Reading Emily Dickinson to the music of The Doors

“You will be haunted by some shadows of the past falling across the page of present”, read a fortune cookie last night, spilling the future for you after a meal of Kung-Pao chicken. Fuck fortune cookies. A man makes his own fortune. Or does he? Nothing however seems to be lost in you however does it, especially the bitterness that you have sieved through your brain again and again, triple distilled?

It has begun to rain and you need to stop drinking and get out of this god-forsaken bar. Solitude of your mind has become a precious solitaire that is rarely shattered, even as you sleep walk your way through dim blues joints inside this brown pelt of yours, many nights of the week. That familiar penetrating wail of a guitar, the band is covering The Doors, goddamn how can you break on to the other side, when you seem to find a new side every time you wake up, from whichever floor you find yourself lying on.

I hide myself within my flower That fading from your Vase, You, unsuspecting, feel for me – Almost a loneliness. ~Emily Dickinson (903)

“Boil it down, boil it down” urges a poet, the sinew of your chest, the fat of your heart, but the great rage and great pain you find growing inside, so naturally, in your vase don’t somehow permit that. What does one feel then? Almost a loneliness? Or as Dickinson spake, a formal feeling?

After great pain, a formal feeling comes – The nerves sit ceremonious like tombs.

How did a reclusive genius write such words, which could have been the wail of a blues song? What is this music but flowers hurled at the nerves, those tombs from which a hand occasionally reaches for the sky, passing feet, laughing children, sunshine, first flowers of spring, and feeds the lipless grinning mouth inside, words that perhaps were just blowing in the wind all along?

This music spills out of the hands out the waitress over there in the steely light, bent over folding (Aw child! how she folds) pieces of steel, on which food reaches your mouth, between pieces of square paper, on which you scribble these words. Roadhouse Blues, streaks of red in her black hair, streaks of vanished tears down her face. Why are you reading your fucking wretchedness into the scenery, Brother? The howl of stark raving best minds of a generation is too distant in time now.

To whom the Mornings stand for Nights, What must the Midnights be! ~Emily Dickinson (1055)

Ah midnight, ah how sweetly passes midnight, casting long shadows across your face. Hello, I love you. Won’t you tell me your name? Or is this The End? Yes yes yes…

My Daily Notes

... link (no comments) ... comment

Valentine’s Day Poem

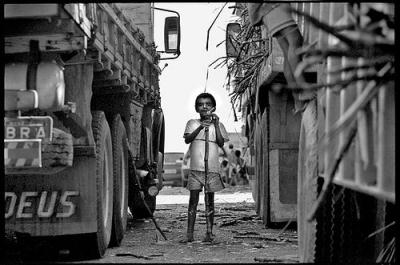

It must be raining in Alagoas.I can hear the roar of water falling Falling As convoys of trucks, headlights gleaming Like fireflies, slither and crawl into a night Of vanished toucans, carrying away Carrying away your cheaply sold Long long hair.

O! These wounds they leave. O! These scalped and mute Gullied hilltops. Here teeth fall out by twenty or so And young women with lined faces Line the slave queues for any work. Lord, we pray for our daily bread. Lord, we pray for our death daily.

They make a desolation and call It progress. They make a desolation and call It development.

But what do children know of these games That suited ghosts in barricaded glass forts play? What do they know of cloudy statistics? Moody Ratings? Fickle capital flows?

Here future is the next uncertain meal. Here days hopscotch between the gaps Of death’s teeth. Here the face of god is Sugarcane falling from a stalled truck.

And here I am walking, with my arms Spread wide, Not like a prophet who promises Salvation or heaven – there is neither, But as a man who still suffers some, Into the as yet undivided, as yet unsold country of rain, To embrace you, my raped Alagoas.

All the above photographs © Tatiana Cardeal. Please click on the link to see more haunting photographs, and read commentry by Tatiana on the making of these photographs.

Notes: Jean Paul Sartre said literature should change the world and that writing is the most serious thing in the world. However I don’t know if it can, because to change the world takes two hands, like those of Zorba’s. So here, as I struggle to climb and claw my way into one of those high glass forts, when other realities sometimes slam into my scrubbed windscreen like bats, like night critters, I scream.

Why do I scream? Is it in some kind of horror, which is in some perverse way pleasurable – as people scream here, in dark theatres while they watch movies titled ‘Texas Chainsaw Massacre’ etc, or in one of the gladiatorial arenas during traffic stopping events called ‘Super Bowl’ or ‘Monster Truck Madness’? In relief that it is they, those others, and not me? Is it to express some useless solidarity with the hungry, huddled and suffering masses at whom Lady Liberty now, mostly, winks? Would it be better if I simply remained silent?

Image-ned Word

... link (no comments) ... comment

Next page